PISA-envy, Pearson and Starbucks-style schools

Adam Unwin and John Yandell explain how international testing and privatizing education go hand in hand.

Source: New Internationalist (April, 2016)

The focus on test scores is vital to the neoliberal vision of education. It is what enables standardization and hence accountability across the system. If outcomes in the form of test scores are what counts, then it becomes easy to compare one student with another, one class with another, one school with another and one state with another. And test-based accountability has now become a truly global phenomenon, shaping local and national educational priorities and policies.

Since 2000, more and more countries have participated in the periodic PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) tests, administered by the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). These tests, in reading, mathematics and science, are taken every three years by 15-year-olds. Increasingly, the PISA league tables drive education policy. PISA-envy inspires governments to look to higher-performing countries for solutions, ways of addressing their own schools’ perceived shortcomings.

The assumption that informs such panic-stricken responses to any slide down the league tables is that context is irrelevant – that what works well in one jurisdiction can simply be imported into another. If it works in Shanghai, then it’s just what Washington needs.

This is a pretty daft way of developing education policy. It simply isn’t feasible to isolate one aspect of how schooling is done in one culture, one society, and introduce it into a completely different culture and society. Moreover, it seems clear that the PISA factor leads to a narrowing of the curriculum: what is important is what is to be tested, and this becomes the focus of attention, of time and resources, while other aspects of curriculum, other dimensions of learning, become marginal.

But PISA is changing – and changing in a way that both mirrors and facilitates the neoliberal mania for privatization. In the early years of PISA, test design, data collection and analysis were all entrusted to international consortia of professional organizations. In 2013, the OECD awarded the contract for the administration of their tests in the US to McGraw-Hill Education, the giant textbook and testing company. In 2014, however, the OECD gave the contract for developing the frameworks for PISA 2018 to Pearson, the largest education company in the world: Pearson will determine what is to be tested and how. It is worth looking carefully at the role that Pearson is now playing in education, particularly in the Global South.

Always earning

In July 2015, Pearson sold the Financial Times to a Japanese company, Nikkei. John Fallon, the head of Pearson, explained the decision to sell the internationally respected newspaper that had been part of the Pearson portfolio for 58 years. The FT contributed less than £25 million ($40 million) to the company’s annual profits of around £800 million ($1.3 billion).1

Pearson, with an annual turnover of nearly $8 billion, had made the decision to focus exclusively on education. This was not out of some sense of civic responsibility; it came from a hard-headed business assessment of where the profits were to be made. Its strapline may be ‘always learning’ but, as other commentators have suggested, it might more aptly be ‘always earning’.

Pearson’s involvement in education is nothing new. It produces textbooks and test papers, online learning materials and educational software and has a large consultancy operation. In the past decade, however, it has become a truly global player, with over 40,000 employees operating in over 80 countries.2 It is in this context that the award of the contract for PISA 2018 needs to be seen. What Pearson is already doing – very successfully – is simultaneously influencing educational policy and providing solutions for the problems which it identifies (and thus creating opportunities for further profit-making interventions).

In 2011, Pearson appointed Sir Michael Barber as its Chief Education Adviser. Barber, who had been working for McKinsey (another education consultancy firm), came to prominence as head of UK Prime Minister Tony Blair’s delivery unit, where he had developed ‘deliverology’, his uncompromising, outcomes-focused, market-based approach to public policy.3

In government, Barber was massively influential in promoting an approach based on the assumed superiority of the private sector, so that entrepreneurial innovation was to remedy the deficiencies and failures of the old, monolithic public services. He was, therefore, the perfect recruit for companies seeking to promote for-profit alternatives to public schooling. In 2012, Barber launched the Pearson Affordable Learning Fund (PALF) as a for-profit venture fund to support the development of low-fee private schools in African and Asian countries – particularly in high-growth emerging markets such as India, Pakistan, South Africa, Kenya, Ghana and the Philippines.

Pearson bought into Bridge International Academies (BIA), a for-profit chain with 400 schools already opened in Kenya as well as seven in Uganda, and plans for further expansion in Nigeria and India, with the aim of catering for 10 million students by 2015. What is significant about this venture is, of course, the scale – and it is this which drives Pearson’s investment strategy. But equally striking is the version of schooling that it represents:

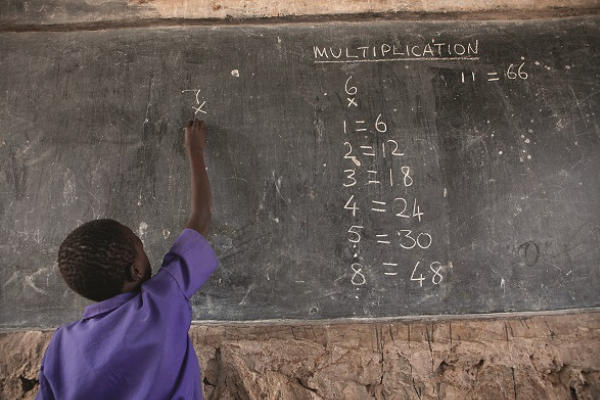

The strategic feature of BIA’s business model is based on a vertically integrated Academy-in-a-box model (also referred to as ‘Starbucks-style’ schooling). This involves a radical standardization of processes and methods, including curriculum and pedagogy, and a heavy reliance on data analytics and technology that enable the company to expand rapidly and achieve huge economies of scale. A scripted curriculum, providing instructions for and explanations of what teachers should do and say during any given moment of a class, is delivered through tablets synchronized with BIA headquarters for lesson plan pacing, monitoring and assessment tracking.2

What BIA offers is thus the apotheosis of neoliberal education: privatized, centrally controlled and outcomes-focused. Its cost-effectiveness is assured, not only by the economies of scale but also because of its unique selling point: who needs a qualified teacher when you can have a tablet?

Pearson, like other edu-businesses seeking to expand into hitherto under-developed areas of the market, have made large claims for the success of the low-fee private schools: that they reach the poorest children, those who have not had any experience of schooling; that they are more efficient than the public schools with which they are in competition; that they produce better results, higher standards.

Undermining provision

There is very little independent research supporting most of these claims, and the most rigorous examination of the evidence available so far casts considerable doubt on them.4 Rather than providing schooling for those children who have not had access to it, it would seem that the low-fee schools are operating in competition with the state schools, thereby further undermining existing provision.

But this argument is, in any case, not one that can be resolved by more objective evaluation data, since it depends on your view of what education is and what it is for. If education is a commodity, deliverable with the aid of scripted lessons and the rest of the paraphernalia of an ‘Academy-in-a-box’ and measurable through a few simple standardized tests, then there’s probably nothing to worry about. Pearson will indeed be always learning – and always earning.

If, on the other hand, education that is worth the name is not reducible to these processes and these products, then we need to consider some alternatives to the goods that John Fallon and Michael Barber are selling us.